Search for answers or browse our Knowledge Base.

Guides | Models | Validation | Book

Electric Field Integral Equation

The foundation of modern antenna simulation lies in solving the Electric Field Integral Equation (EFIE). For metallic structures with ideal conductivity, the EFIE relates the incident electromagnetic wave to the currents induced on the surface of the object.

The Fundamental Equation

In the frequency domain, the EFIE is expressed as follows:

$\displaystyle \hat{\mathbf{n}} \times \left[ j \omega \mu_0 \int_S \mathbf{J}_s(\mathbf{r}’) \, G(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{r}’) \, d^2\mathbf{r}’ + \frac{j}{\omega \varepsilon_0} \nabla \int_S \nabla’ \cdot \mathbf{J}_s(\mathbf{r}’) \, G(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{r}’) \, d^2\mathbf{r}’ \right] = \hat{\mathbf{n}} \times \mathbf{E}^{\text{inc}}(\mathbf{r}) \quad (1)$

Where:

- $\mathbf{E}^{\text{inc}}$: The incident electric field on the PEC (Perfect Electrical Conductor) surface $S$.

- $\hat{\mathbf{n}}$: The unit vector normal to the surface at the observation point $\mathbf{r}$.

- $\mathbf{J}_s(\mathbf{r}’)$: The unknown surface electric current density at the source point $\mathbf{r}’$.

- $G$: The free-space Green’s function.

The free-space Green’s function is given by:

$\displaystyle G(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{r}’) \,=\, \frac{e^{-j k R}}{4 \pi R} \qquad (2)$

where $R = |\mathbf{r} \,-\, \mathbf{r}’|$ is the distance between the source and observation points.

As usual, $k = \omega/c$ is the wavenumber, $\omega = 2\pi f$ is the angular frequency, $f$ is the frequency in Hertz (Hz), and $c = 1/\sqrt{\mu_0 \varepsilon_0}$ is the speed of light in free space. The permeability and permittivity of free space are denoted by $\mu_0$ and $\varepsilon_0$, respectively. The free-space wavelength is defined as $\lambda = c/f$.

The EFIE expresses the boundary condition on a surface $S$, which is assumed to be a Perfect Electrical Conductor (PEC); specifically, it enforces a zero tangential electric field on that surface.

From Surfaces to Wires

When modeling wire antennas, we assume the wire radius ($a$) is much smaller than the wavelength ($a \ll \lambda$). This allows us to simplify the surface integral into a line integral along the axis of the wire. The resulting equation for a curvilinear wire $C$ is:

$\displaystyle \hat{\mathbf{s}} \cdot \frac{j}{\omega\varepsilon_0} \int_C \left[ k^2 I(s’) K(s,s’) \,\hat{\mathbf{s}}’ \,+\, \frac{d I(s’)}{ds’} \nabla K(s,s’) \right] ds’ \,=\, \hat{\mathbf{s}} \cdot \mathbf{E}^{\text{inc}} \qquad (3)$

where $\hat{\mathbf{s}}$ is the tangential unit vector along the curve $C$. In this specialized form, $I(s’)$ represents the total current flowing along the wire’s path $C$, and $K(s, s’)$ is the Kernel of the integral equation, which is given by:

$\displaystyle K(s,s’) \,=\, \frac{1}{4 \pi^2} \int_0^{2\pi} \int_0^{2\pi} G(\mathbf{r},\mathbf{r}’) \, d\phi’ d\phi \qquad (4)$

where $\phi$ and $\phi’$ represent the angular positions of the observation and source points, respectively, on the wire’s circular cross-section.

By averaging the EFIE over the wire circumference, we obtain the curvilinear EFIE presented in Eq. (3), utilizing the exact kernel defined in Eq. (4).

The current distribution $I(s)$ represents the average value of the surface current density $\mathbf{J}_s$ in the axial direction, while current in the transverse direction is neglected. This remains a valid assumption provided the wire radius is small relative to the wavelength $\lambda$.

Parametric Modeling and the Exact Kernel

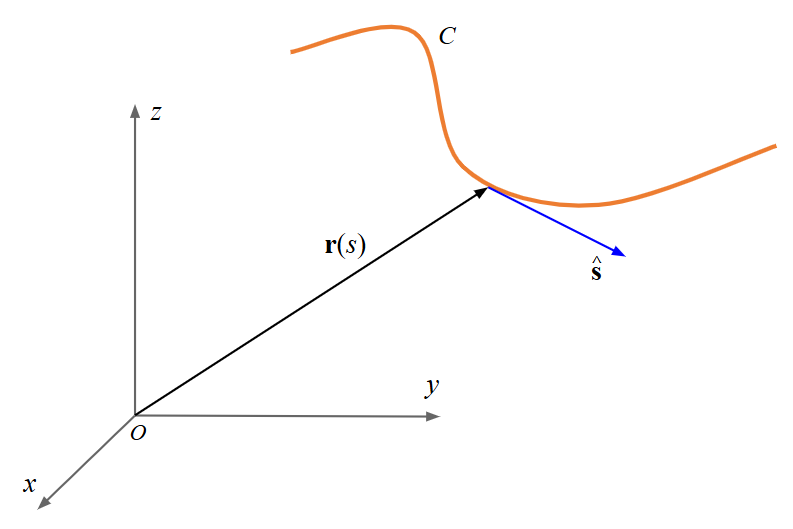

Accurate simulation of curved wires—such as helices, spirals, or loops—requires a parametric description of the wire’s geometry. By defining the position vector $\mathbf{r}(s)$ and its first derivative (the tangent vector), the solver maintains exact geometric information that is lost in traditional straight-wire approximations.

The wire axis $C$ is described by parametric equations, which can be expressed in a Cartesian coordinate system as:

$\displaystyle \mathbf{r}(s) \,=\, \hat{\mathbf{x}}\ x(s) \,+\, \hat{\mathbf{y}}\ y(s) \,+\, \hat{\mathbf{z}}\ z(s) \qquad (5)$

In this equation, $\mathbf{r}(s)$ points from the origin to any point on the wire, as shown in Fig. 1. The parameter $s$ varies over a real interval $s_{\min} \leq s \leq s_{\max}$.

The tangent unit vector $\hat{\mathbf{s}}$ is obtained from the first derivative of Eq. (5):

$\displaystyle \frac{d \mathbf{r}}{ds} \,=\, \hat{\mathbf{x}}\ \frac{dx}{ds} \,+\, \hat{\mathbf{y}}\ \frac{dy}{ds} \,+\, \hat{\mathbf{z}}\ \frac{dz}{ds}\ \implies\ \hat{\mathbf{s}} = \frac{d \mathbf{r}}{ds}\,\Bigg|\frac{d \mathbf{r}}{ds}\Bigg|^{-1} \quad (6)$

This parametric description is essential for the accurate modeling of curvilinear wires and general wire structures. Approximating the geometry with straight-wire segments results in a loss of geometric information that can never be fully restored. However, this information is preserved when a parametric representation is used to describe the wire’s locus.

The Thin-Wire Approximation

In many legacy codes, the exact kernel in Eq. (4) is simplified using the thin-wire approximation (Fig. 2):

$\displaystyle K(s,s’) \approx \frac{e^{-j k R}}{4 \pi R}, \qquad R \,=\, \sqrt{|\mathbf{r}(s) \,-\, \mathbf{r}(s’)|^2 + a^2} \qquad (7)$

where $a$ is the wire radius.

If the wire is straight and $s$ represents the length parameter along the wire, and when the observation point $\mathbf{r}(s)$ and the source point $\mathbf{r}(s’)$ are both on the same straight wire, the distance $R$ reduces to the standard thin-wire approximation for straight wires:

$\displaystyle R \,=\, \sqrt{(s \,-\, s’)^2 + a^2} \qquad (8)$

While this approximation is computationally efficient, it introduces numerical artifacts when segments are very short or when wires are in close proximity. AN-SOF’s use of the Exact Kernel avoids these simplifications, ensuring that the distance $R$ between source and observation points is calculated precisely across the entire tubular surface of the wire. This approach leads to superior convergence and numerical stability.